Research

Speaking mame-loshn: Maternal Affect and Yiddish Modernity

My dissertation focuses on readings of the Tsenerene, Yiddish lullabies, and Yiddish children’s primers through the prism of the cultural imaginary of the mameloshn (“mother tongue,” also an affectionate name for the Yiddish language). The word plainly associates the language with maternity and by implication, with children and childhood. For more than a century, proponents of Yiddish culture have attempted to distance the language from such unserious, homely, and unsophisticated associations. While the Jewish Enlightenment of the late nineteenth century viewed Yiddish as the unrefined, folksy, and emotional mame-loshn, later proponents of modern Yiddish culture actively resisted this narrative and molded the language into a vessel for high art and culture. In the process, they banished the thought of Yiddish as feminine or childish. A consequence is that Old Yiddish literature for women, Yiddish folk songs from the female repertoire, and Yiddish literature for children remain under-researched. A crucial question emerges: what kind of affective relationship does a mame-loshn forge between a people and its language? The mame-loshn is a prism through which to understand how and why the culture redefined itself as it encountered modernity.

Tsenerene: A “women’s Bible”?

The seventeenth-century bestseller known as the “women’s Bible” conjures images of generations of wizened grandmothers weeping over their beloved book on Shabbes afternoons. But whose images are these? And what do they tell us about the historiography of Yiddish literature and its audiences?

My research addresses the development of myths around the Tsenerene that trendered it a “women’s Bible,” even a “womanly” Bible. What is the effect of establishing literature as “women’s,” or as “womanly”? I trace the origins of the moniker “vaybershe bibl” to no earlier than the 1910s, an extraordinarily generative moment for reappraisals of Yiddish literary history that elevated some literature (and its readers) and diminished others in order to assert a respectable lineage for the literature of the mame-loshn.

Ruth Rubin and Yiddish Folk Song in America

Ruth Rubin was a luminary in the collection and dissemination of Yiddish folk song and lore. Beginning in the 1940s and spanning the next four decades, Rubin meticulously gathered over 2,000 songs and other folkloric material from Jewish immigrants in New York, Toronto, and Montreal. What sets her apart is not just her extensive collection, but how she ingeniously revitalized the folklore of Eastern European Jews, restoring it from an arcane academic topic to the bedrock of modern Jewish culture. I am tracing the way Rubin understood folk song to be a vibrant source of Jewish knowledge and culture, especially in the aftermath of the Holocaust, and in conversation with the rise of representations of Jews in popular American media.

One of the most extraordinary things about Ruth Rubin is also the most obvious: she was a woman. She was one of the first women in the field of Jewish folklore and the first to emerge from a North American environment, facts that deeply shaped her perspective. Despite her lack of formal education or training, or perhaps because of it, Rubin was able to navigate both popular and academic discourses on folklore, crossing easily between the two in her published writing, her LPs for Folkways Records, and her signature lecture-performances. In these ways, Rubin offered a lens through which to view Eastern European Jewish culture and society, and also served as the embodiment of that culture, at a time when American audiences were increasingly distant from it.

This research places Rubin’s work at the intersection of the American feminist movement, post-Holocaust Jewish memory, the legacies of Yiddishism, and the sublimated tensions and traumas of her own biography. It interweaves critical biography with cultural history, following Rubin from her childhood home in Yiddish Montreal to spaces of Rubin’s artistic and scholarly growth—her own modest Gramercy Park apartment, the communal spaces where she encountered her informants, and the myriad public spaces where she interpreted and performed the songs she collected. Rubin’s investment in the figures of children and women operated in symbolic relation to collective touchstones that impacted her perspective—the Holocaust and its devastating aftermath, the American folk music revival, the rise of the feminist movement, and the Yiddish cultural revival.

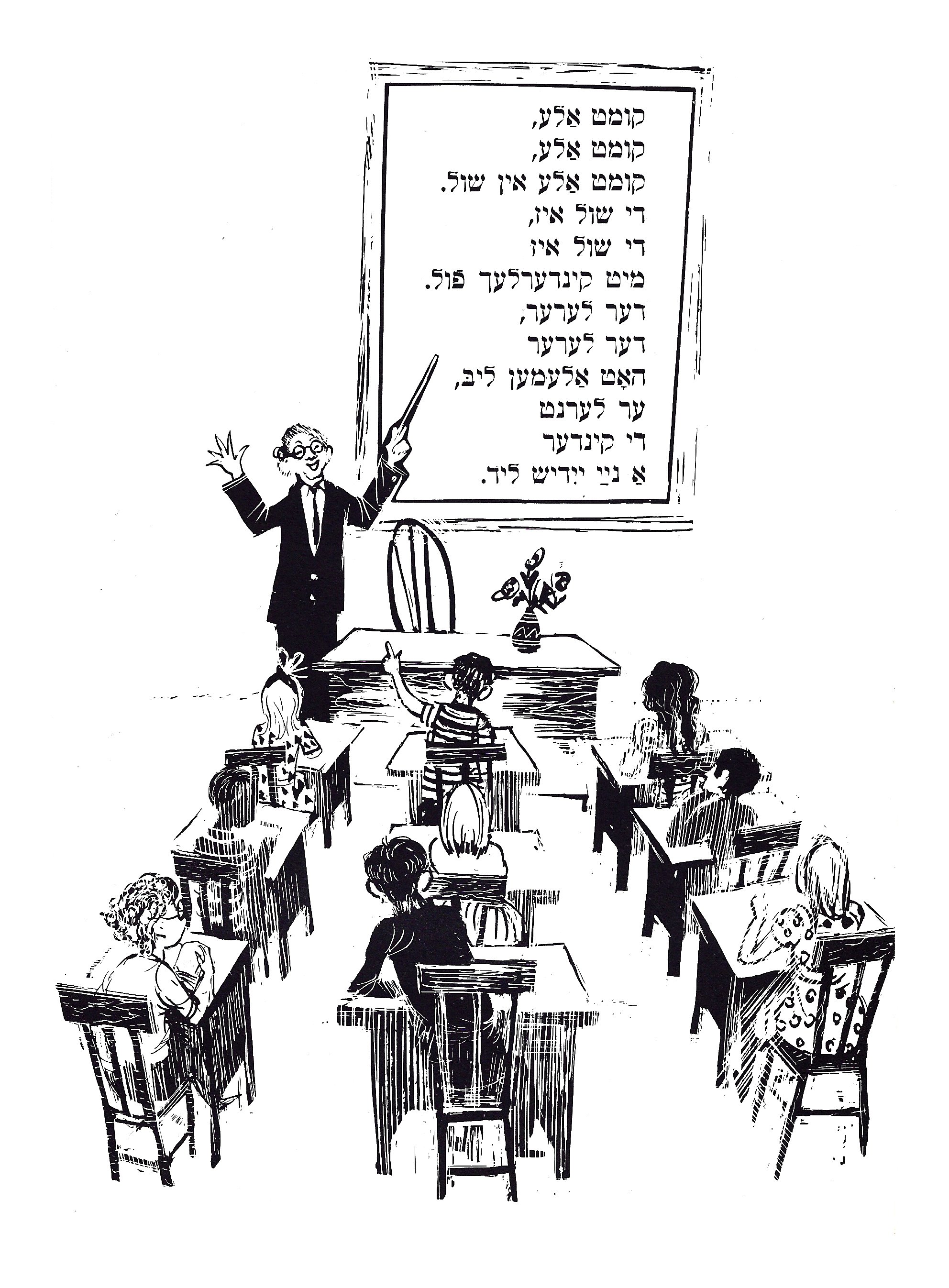

Yiddish in the Post-Holocaust Classroom

Part of a special volume of Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes dedicated to Jewish education in Canada, my recently published article “Joshua, King David, and the Flying Nun: Doodles and Reader Annotations in Post-Holocaust Yiddish Primers for Children” explores humorous and insightful children’s doodles and reader annotations in Yiddish textbooks used by students in Toronto in the 1950s -70s. Constituting a kind of midrash, these annotations offer a window into children’s developing relationship between Yiddish and Jewishness.

These books are deceptively sophisticated texts, and their readers responded in subtle but equally sophisticated ways. Students in Yiddish supplementary schools used texts produced by educators steeped in a diaspora nationalist pedagogy that reflected the ideological coupling of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit: the Yiddish language informed one’s sense of Jewishness. By the 1960s, doodles students left in their schoolbooks challenged this coupling of language and identity. Though it is generally supposed that Yiddish primers ultimately tell us more about the aspirations of adults than they do about the experiences of children, reading these texts together reveals that children evolved their own relationship between Yiddish and Jewishness that was far more subtle than what they encountered in their textbooks. Postwar primers emphasize maintaining the Yiddish language on American soil, to the exclusion of the external culture; children’s doodles argue that more important than preserving the language was locating Yiddishkeit in the culture around them.

At the center of this study is a perhaps perennial question for Yiddish: that of national and social belonging. Images of flags, Stars of David, inscriptions of place and address, scrawls upon maps, and references to television commercials for personal hygiene products—which reflect conceptions about the body and its permissibility in society—appear in the margins and inside covers of these books, indicating that students possessed an awareness of the signs and symbols that formed the building blocks of national narratives undergirding both their Yiddish textbooks and the wider culture they inhabited. Doodles are a rough draft, not the finished product. They are a way of testing and rehearsing ideas, exercises in experimentation at a particular moment. They are raw, unhindered, and unprocessed, and reading them carefully illuminates the depth of their dimension.