Miriam Borden

doctoral candidate

I’m Miriam Borden, a scholar and researcher of Yiddish Studies specializing in Ashkenazi Jewish literature, folklore, and post-Holocaust Yiddish culture.

@bikher_chick - Illustrations, excerpts and logos from the world of Yiddish booksWeekly #yiddishwordoftheweek posts on the Ontario Jewish Archives Instagram

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden

RESEARCH

Speaking mame-loshn: Maternal Affect and Yiddish Modernity

My dissertation focuses on readings of the Tsenerene, Yiddish lullabies, and Yiddish children’s primers through the prism of the cultural imaginary of the mameloshn (“mother tongue,” also an affectionate name for the Yiddish language). The word plainly associates the language with maternity and by implication, with children and childhood. For more than a century, proponents of Yiddish culture have attempted to distance the language from such unserious, homely, and unsophisticated associations. While the Jewish Enlightenment of the late nineteenth century viewed Yiddish as the unrefined, folksy, and emotional mame-loshn, later proponents of modern Yiddish culture actively resisted this narrative and molded the language into a vessel for high art and culture. In the process, they banished the thought of Yiddish as feminine or childish. A consequence is that Old Yiddish literature for women, Yiddish folk songs from the female repertoire, and Yiddish literature for children remain under-researched. A crucial question emerges: what kind of affective relationship does a mame-loshn forge between a people and its language? The mame-loshn is a prism through which to understand how and why the culture redefined itself as it encountered modernity.

Tsenerene: A “women’s Bible”?

The seventeenth-century bestseller known as the “women’s Bible” conjures images of generations of wizened grandmothers weeping over their beloved book on Shabbes afternoons. But whose images are these? And what do they tell us about the historiography of Yiddish literature and its audiences?My research addresses the development of myths around the Tsenerene that trendered it a “women’s Bible,” even a “womanly” Bible. What is the effect of establishing literature as “women’s,” or as “womanly”? I trace the origins of the moniker “vaybershe bibl” to no earlier than the 1910s, an extraordinarily generative moment for reappraisals of Yiddish literary history that elevated some literature (and its readers) and diminished others in order to assert a respectable lineage for the literature of the mame-loshn.

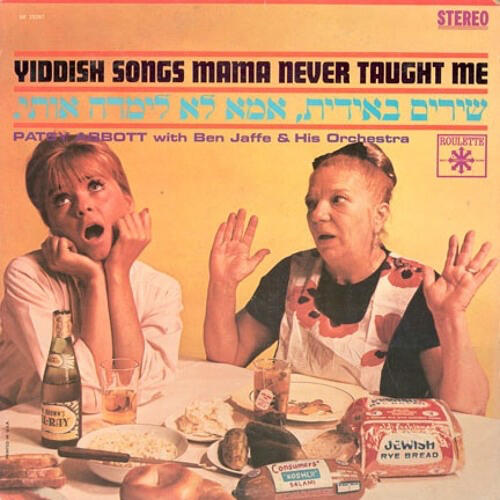

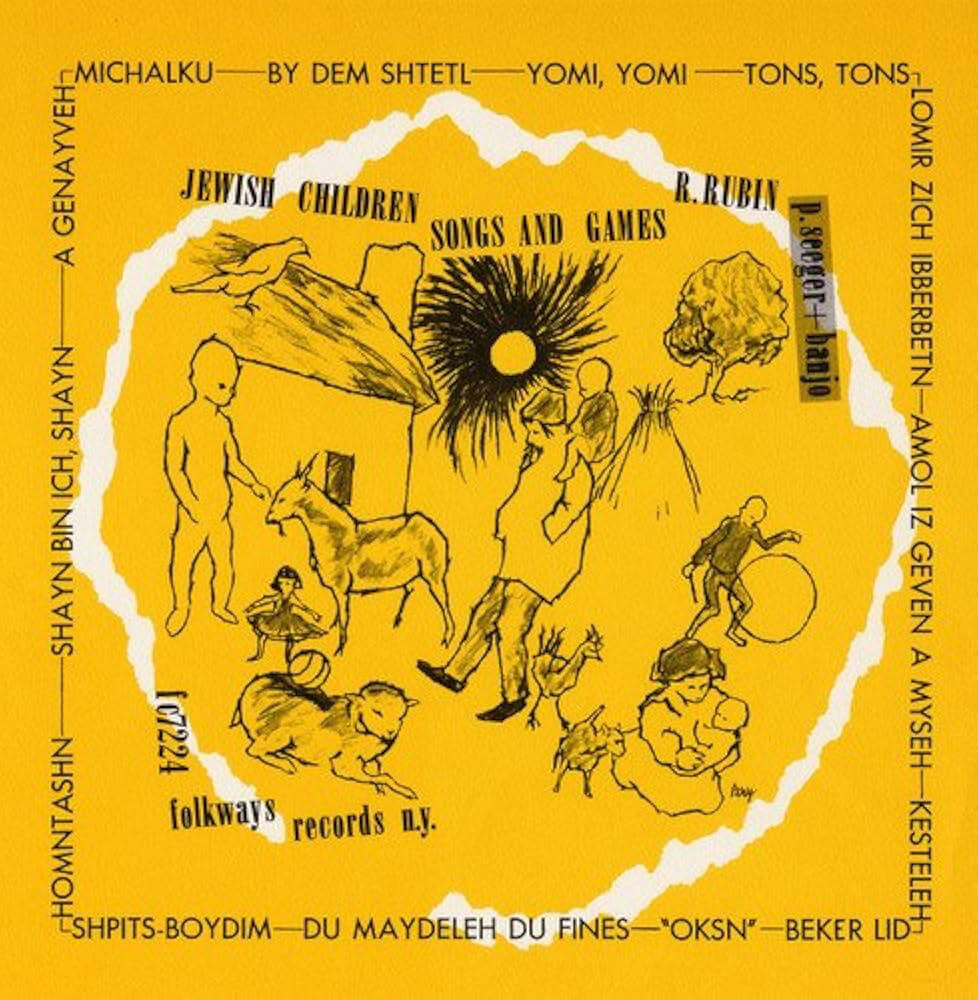

Ruth Rubin and Yiddish Folk Song in America

Ruth Rubin was a luminary in the collection and dissemination of Yiddish folk song and lore. Beginning in the 1940s and spanning the next four decades, Rubin meticulously gathered over 2,000 songs and other folkloric material from Jewish immigrants in New York, Toronto, and Montreal. What sets her apart is not just her extensive collection, but how she ingeniously revitalized the folklore of Eastern European Jews, restoring it from an arcane academic topic to the bedrock of modern Jewish culture. I am tracing the way Rubin understood folk song to be a vibrant source of Jewish knowledge and culture, especially in the aftermath of the Holocaust, and in conversation with the rise of representations of Jews in popular American media.One of the most extraordinary things about Ruth Rubin is also the most obvious: she was a woman. She was one of the first women in the field of Jewish folklore and the first to emerge from a North American environment, facts that deeply shaped her perspective. Despite her lack of formal education or training, or perhaps because of it, Rubin was able to navigate both popular and academic discourses on folklore, crossing easily between the two in her published writing, her LPs for Folkways Records, and her signature lecture-performances. In these ways, Rubin offered a lens through which to view Eastern European Jewish culture and society, and also served as the embodiment of that culture, at a time when American audiences were increasingly distant from it.This research places Rubin’s work at the intersection of the American feminist movement, post-Holocaust Jewish memory, the legacies of Yiddishism, and the sublimated tensions and traumas of her own biography. It interweaves critical biography with cultural history, following Rubin from her childhood home in Yiddish Montreal to spaces of Rubin’s artistic and scholarly growth—her own modest Gramercy Park apartment, the communal spaces where she encountered her informants, and the myriad public spaces where she interpreted and performed the songs she collected. Rubin’s investment in the figures of children and women operated in symbolic relation to collective touchstones that impacted her perspective—the Holocaust and its devastating aftermath, the American folk music revival, the rise of the feminist movement, and the Yiddish cultural revival.

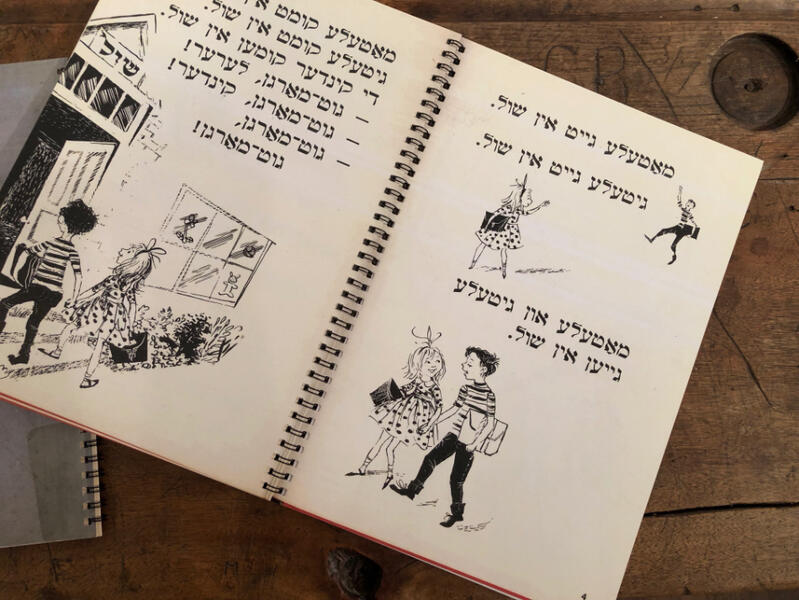

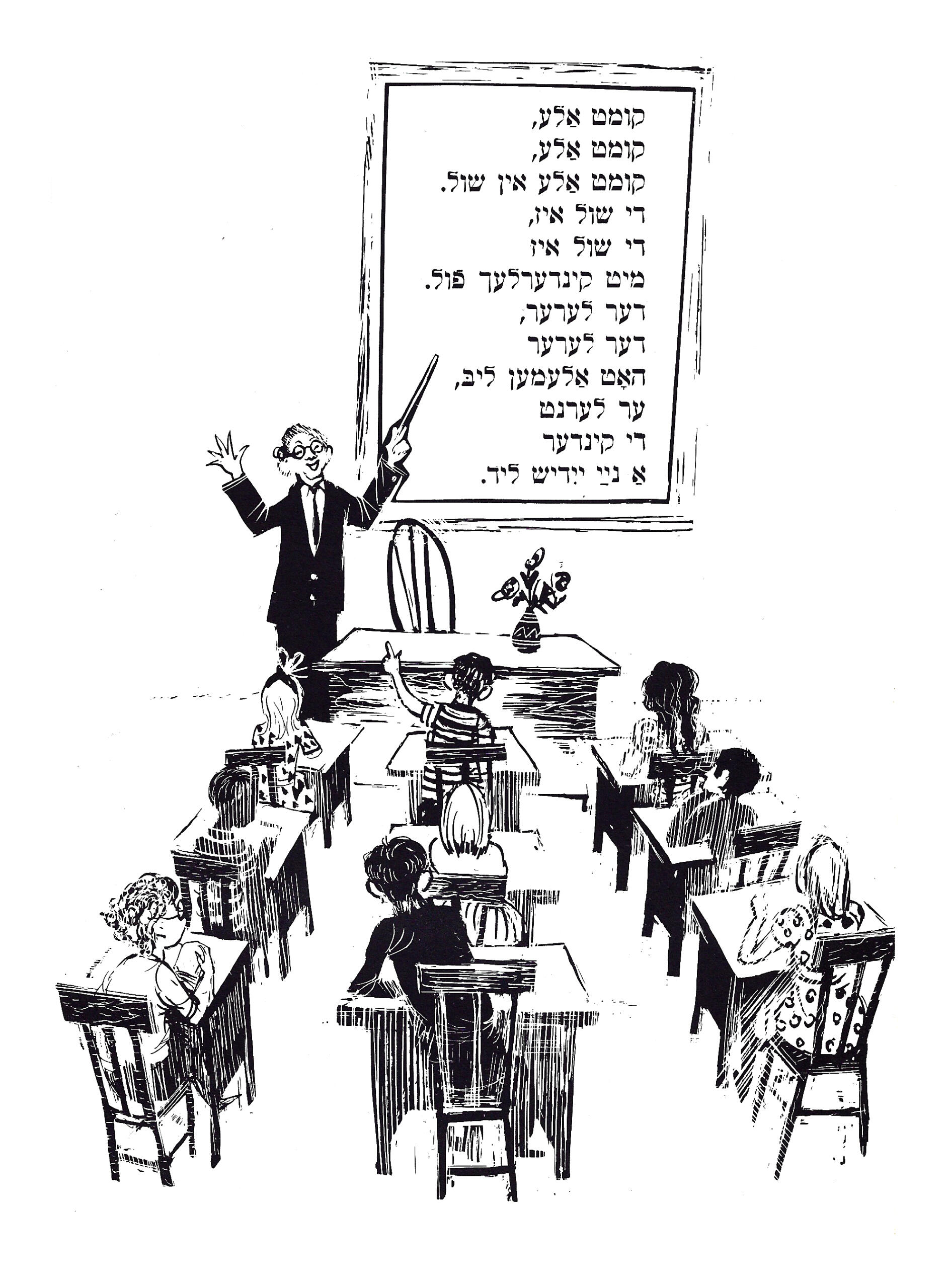

Yiddish in the Post-Holocaust Classroom

Part of a special volume of Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes dedicated to Jewish education in Canada, my recently published article “Joshua, King David, and the Flying Nun: Doodles and Reader Annotations in Post-Holocaust Yiddish Primers for Children” explores humorous and insightful children’s doodles and reader annotations in Yiddish textbooks used by students in Toronto in the 1950s -70s. Constituting a kind of midrash, these annotations offer a window into children’s developing relationship between Yiddish and Jewishness.These books are deceptively sophisticated texts, and their readers responded in subtle but equally sophisticated ways. Students in Yiddish supplementary schools used texts produced by educators steeped in a diaspora nationalist pedagogy that reflected the ideological coupling of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit: the Yiddish language informed one’s sense of Jewishness. By the 1960s, doodles students left in their schoolbooks challenged this coupling of language and identity. Though it is generally supposed that Yiddish primers ultimately tell us more about the aspirations of adults than they do about the experiences of children, reading these texts together reveals that children evolved their own relationship between Yiddish and Jewishness that was far more subtle than what they encountered in their textbooks. Postwar primers emphasize maintaining the Yiddish language on American soil, to the exclusion of the external culture; children’s doodles argue that more important than preserving the language was locating Yiddishkeit in the culture around them.At the center of this study is a perhaps perennial question for Yiddish: that of national and social belonging. Images of flags, Stars of David, inscriptions of place and address, scrawls upon maps, and references to television commercials for personal hygiene products—which reflect conceptions about the body and its permissibility in society—appear in the margins and inside covers of these books, indicating that students possessed an awareness of the signs and symbols that formed the building blocks of national narratives undergirding both their Yiddish textbooks and the wider culture they inhabited. Doodles are a rough draft, not the finished product. They are a way of testing and rehearsing ideas, exercises in experimentation at a particular moment. They are raw, unhindered, and unprocessed, and reading them carefully illuminates the depth of their dimension.

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden

TEACHING

University of California, Berkeley

History of Yiddish Culture

Yiddish is the key to a thousand years of Jewish history. This course asks “Who are the Jewish people?” and finds one answer to that question in the history of Yiddish culture. We trace the development of Yiddish culture from the first settlement of Jews in German lands through centuries of life in Eastern Europe, down to the main cultural centers today in Israel and the United States. The course examines how challenges to Ashkenazi Jewish have found expression in the Yiddish language. It provides an introduction to Yiddish literature in English translation, supplemented by excursions into Yiddish music, folklore, theater, and film.We proceed thematically, taking a transnational perspective of works produced in Eastern Europe, North and South America, and Israel, in centers and in peripheries. We consider the Jewish encounter with travel, exile, race, violence, and politics across several centuries, especially in the modern period. And we consider more recent representations—and reinventions—of Yiddish culture in contemporary film, television, digital media, and popular culture.

University of Toronto

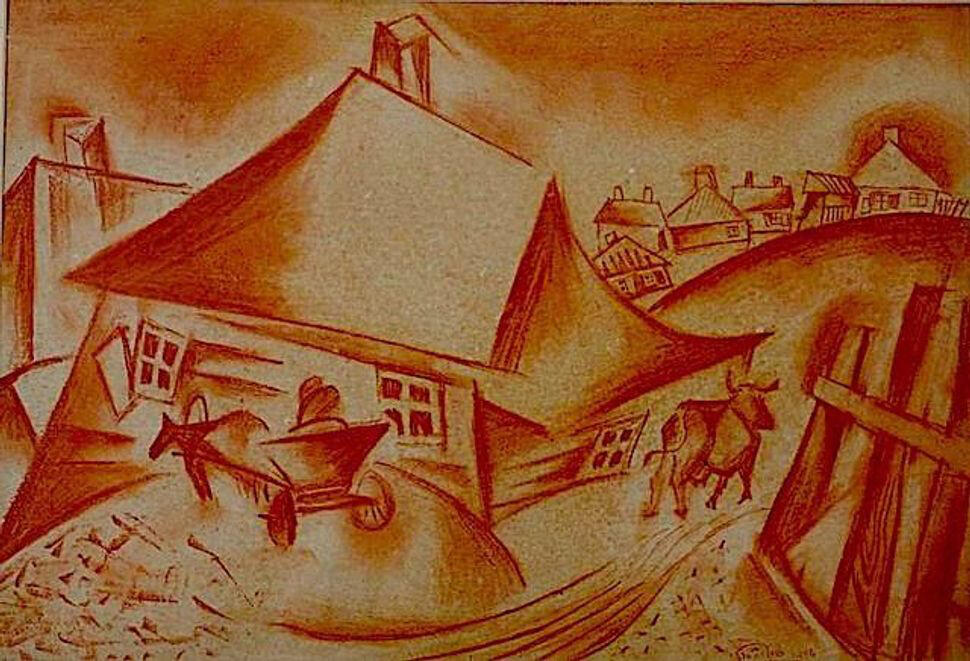

Writing, Remembering, and Imagining the Shtetl

What is a Jewish shtetl? How does it differ from a Jewish city? And how have these been imagined, remembered, and recreated in Yiddish literature? Though Jews in Eastern Europe had called many places home after centuries of settlement and expulsion, by the late nineteenth century modern Yiddish writers found ways of locating Jews squarely (and historically) within the towns and cities in which they lived. Fictional towns and real cities—together comprising the literary territory known as Yiddishland—create a complex geographical map in which Jewish history and memory intertwine. This course take a “tour” of this map, stopping along the way to consider the many ways in which Jewish towns, cities, and other spaces were imagined, negotiated, and continue to be reimagined today.Through close readings of the Jewish town and city in Yiddish literature, we consider the way Jewish spaces—both real and imaginary—were constructed as a vision for Jewish life in two directions: backward, into the past, and forward, into the future. We think about how the city/shtetl itself functions as a literary device that constructs a discrete “world” within a broader narrative. Students will come away with an understanding of how the real and imagined Jewish city/town was constructed through a combination of Yiddish literature and Jewish memory, and how these ideas changed over time. They consider how those literary constructions produced visions both of the Jewish past and of the Jewish future and how those images inform conceptions of Jewish cities, towns, and space today through encounters with museums, monuments, walking tours, and spaces of post-Holocaust Jewish renewal.

University of Toronto

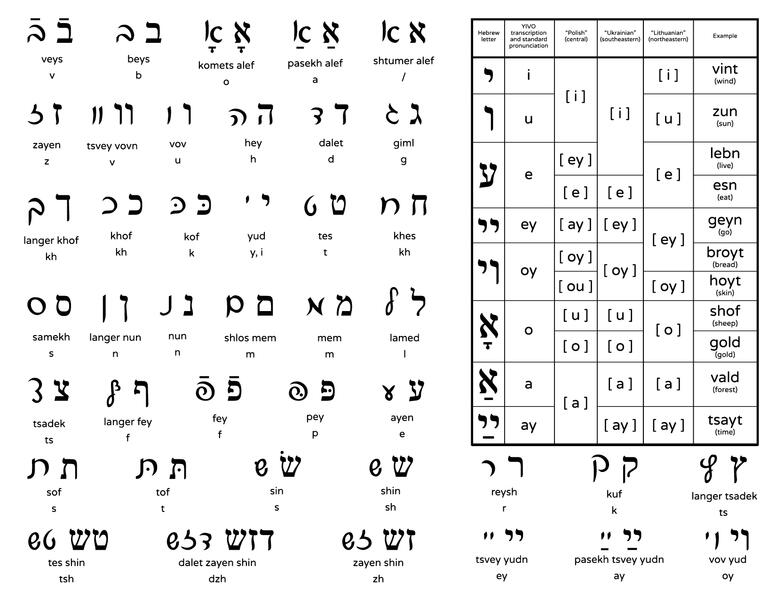

Elementary and Intermediate Yiddish

Grammar, vocabulary, skills in oral communication, basic composition, and critical analysis of literature and culture.

I’d love to teach…

Yiddish in 15 Objects

A transnational, material, and theoretical exploration of some of the major themes, events, and controversies Yiddish culture, language, and society—past and present—through objects: books, maps, advertisements, films, folk songs, photography, tote bags, and more.

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden

exhibitions

I became interested in exhibiting books because I was captivated by the stories they told about Yiddish publishing, Yiddish readerships, and the reception of Yiddish over the span of five centuries of print. And as material objects, they can be breathtaking.I have curated and mounted three exhibitions of Yiddish books from collections at the University of Toronto and the Fisher Rare Book Libraries: “Discovering the Mame-loshn: The Hidden World of Yiddish at Robarts,” (2017) “Komets-alef: O! Back to School at the Yiddish Kheyder” (2018), and an adaptation of the kheyder exhibition for “Yiddish Spring” at the Canadian Language Museum.

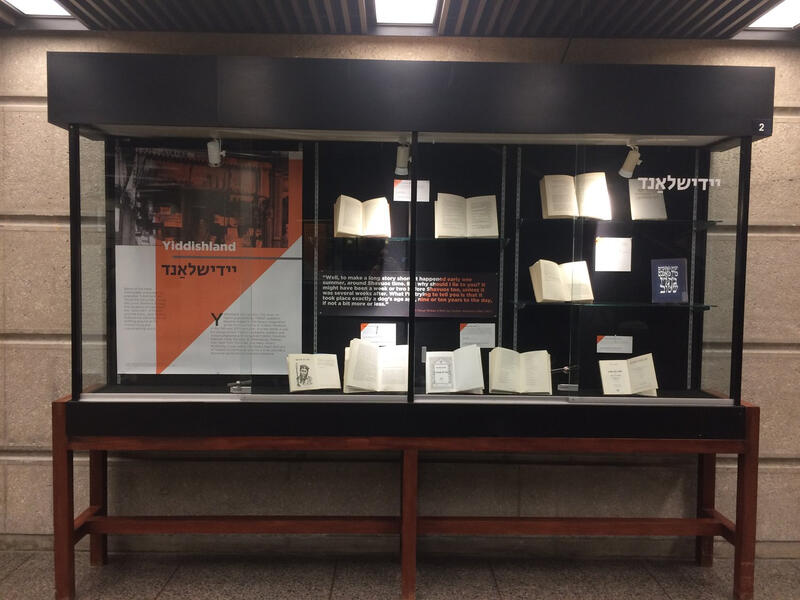

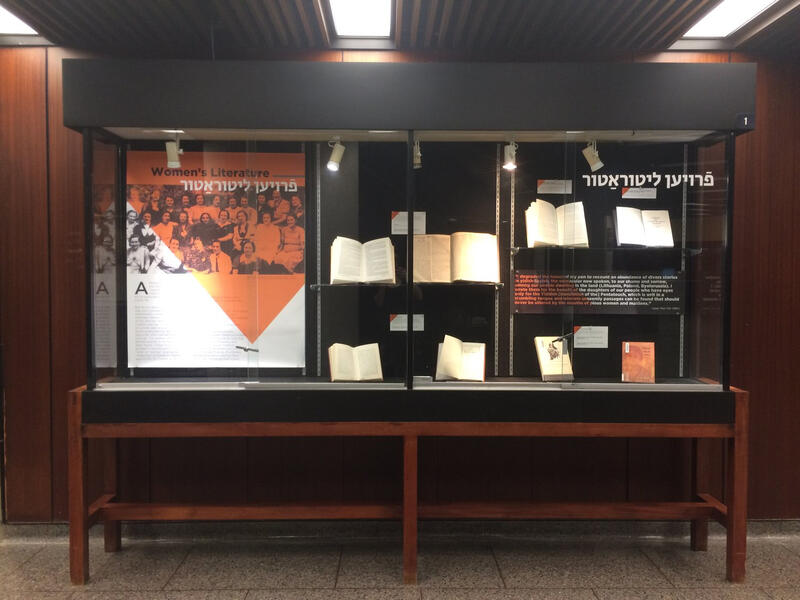

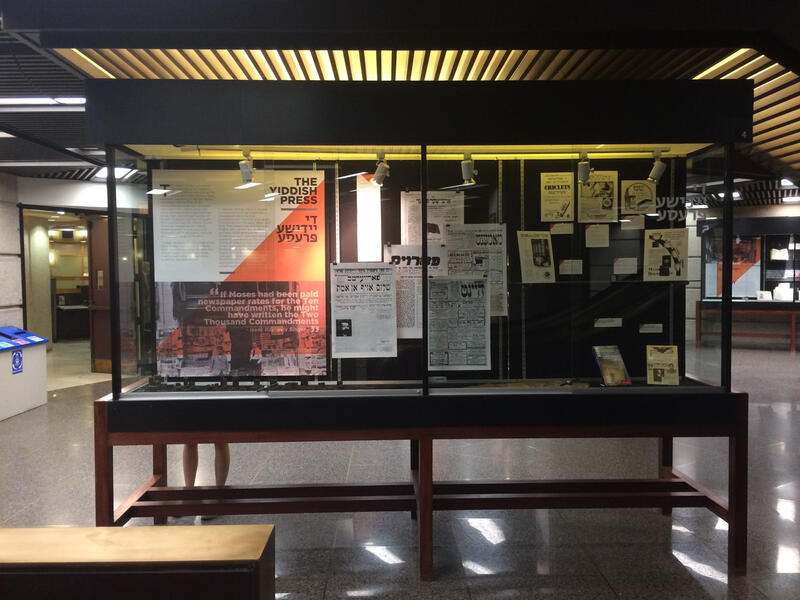

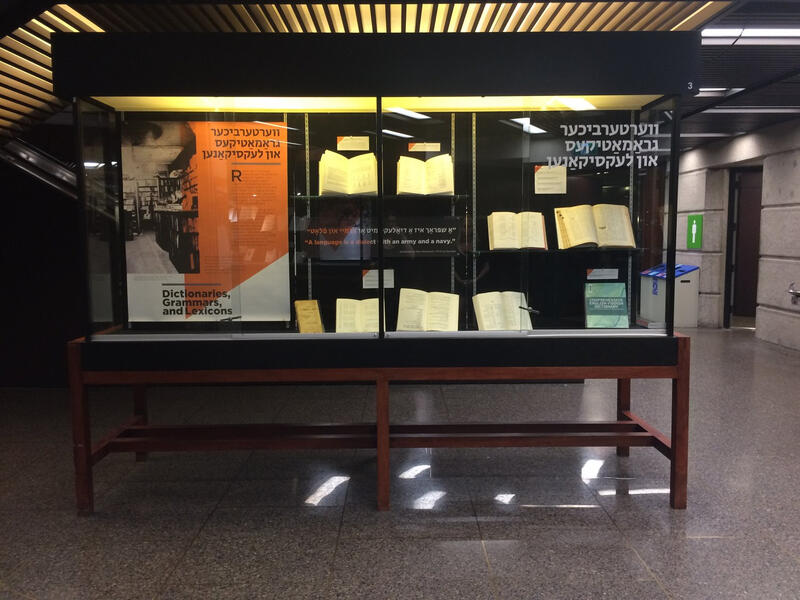

Robarts Library at the University of Toronto, August – September 2017

Discovering the Mame-Loshn

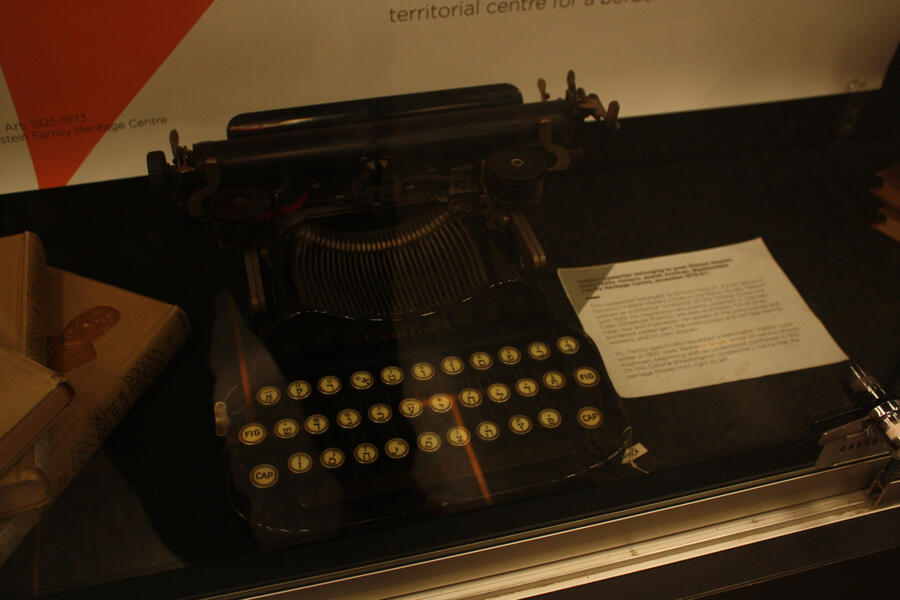

Housed in the five glass cases on the ground floor of Robarts Library, from 1 August – 1 September 2017, Discovering the Mame-loshn: The Hidden World of Yiddish at Robarts revealed the impressive and varied collection of Yiddish materials in the University of Toronto library holdings. On display were a selection of excerpts from the Yiddish press, works for and by women, sacred texts in Yiddish translation, historic volumes of Yiddish dictionaries, and some beloved works from Yiddishland’s rich body of literature.Over 40 books from the library’s collection were on view, as well as original artifacts, including crumbling, yellowed editions of Der Yidisher Zhurnal, the Toronto Yiddish daily newspaper, a collection of Yiddish wooden typesetter’s blocks, anda rare 1920s Yiddish typewriter belonging to Toronto Yiddish poet (and College Street streetcar conductor) Shimon Nepom, on loan from the Ontario Jewish Archives Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre.Though installed at a university library at the peak of the summer break, the exhibit drew record numbers of visitors to Robarts. Library staff were astonished. “We’ve never had this much excitement about a student exhibition here before,” said Neelum Haq, Robarts Access Services Associate. “People calling in, lining up at the Information Desk, asking about hours and admission and whether they could bring family members. It got to the point that they’d approach the desk and say, ‘Can you tell me where the – ‘ and we’d point and say, ‘Yiddish exhibit? It’s that way.’”It was only a small glimpse of the vast Yiddish resources available at the University of Toronto, but it drew enormous attention from both the university community and the public. Due to the overwhelming response the exhibit received, as well as requests for an extension, we created an online presence for the exhibition. That online space has recently evolved into the personal portfolio of Miriam Borden.

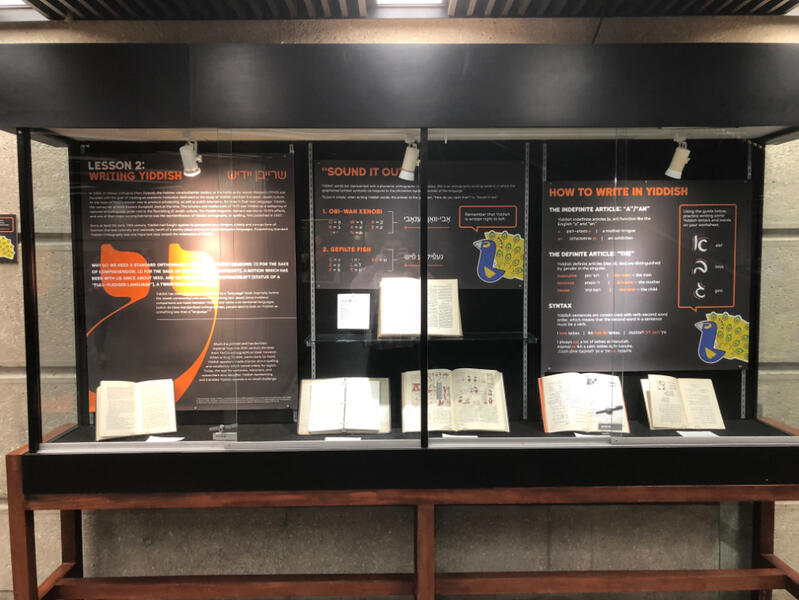

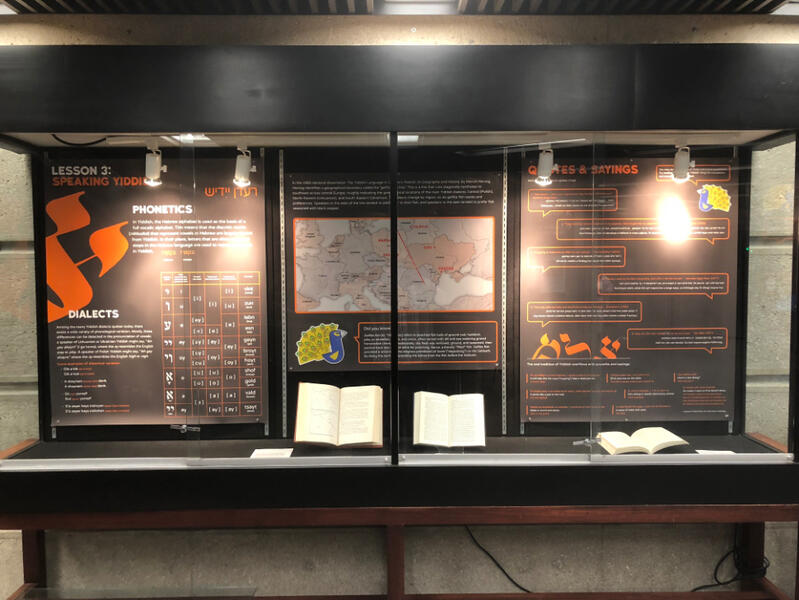

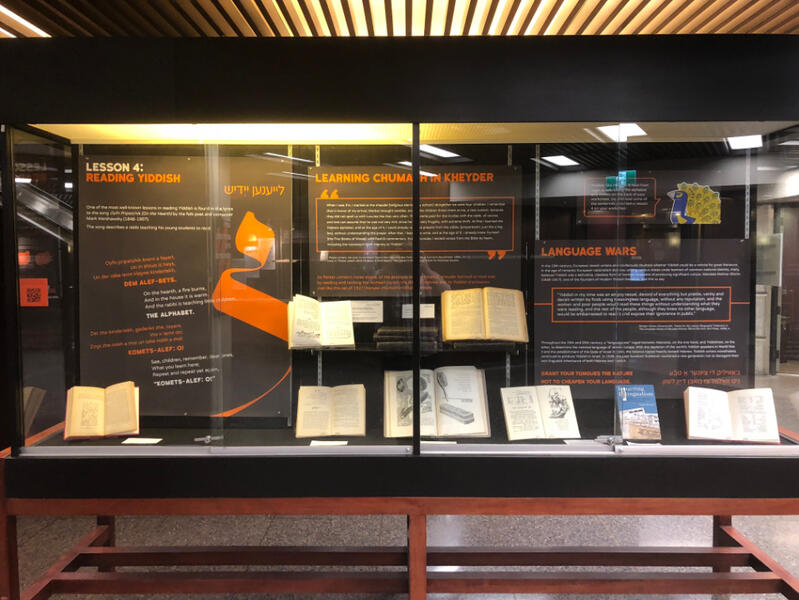

ROBARTS LIBRARY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO, MAY – JULY 2018

KOMETS-ALEF: O!

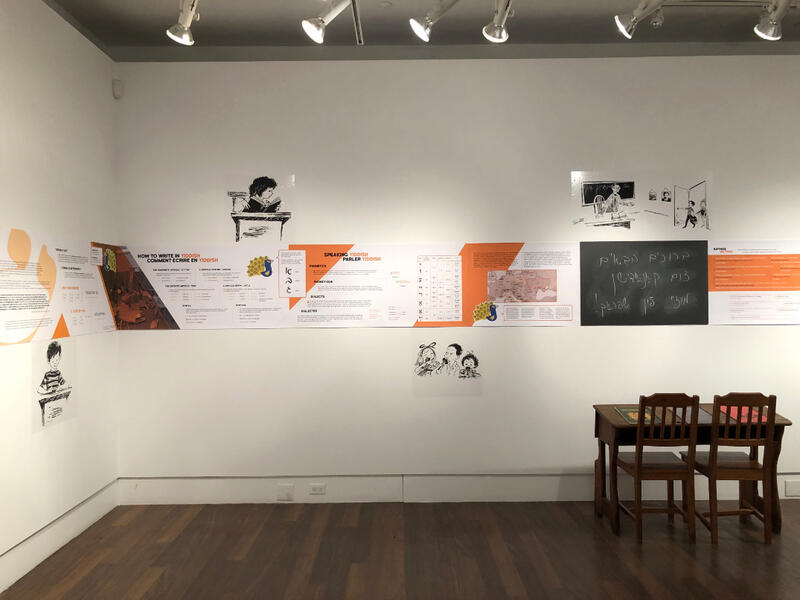

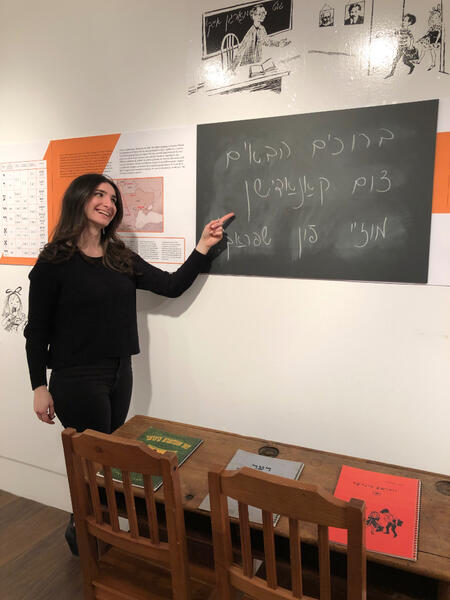

BACK TO SCHOOL AT THE YIDDISH KHEYDER

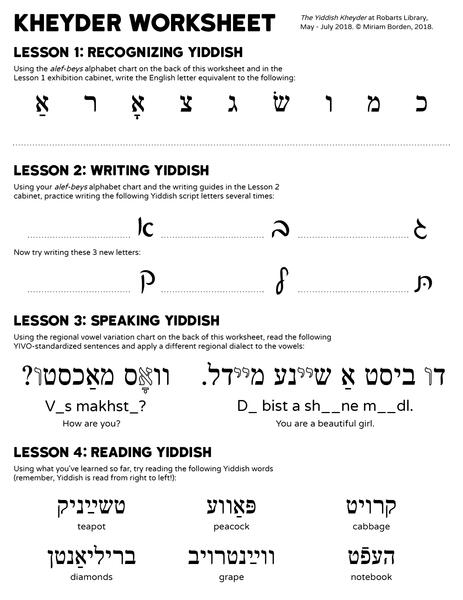

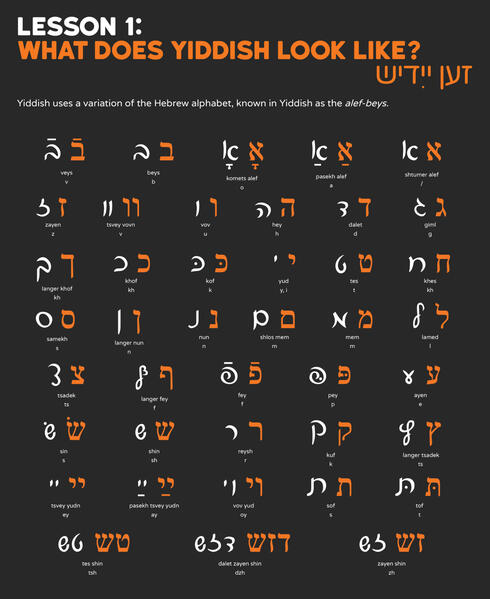

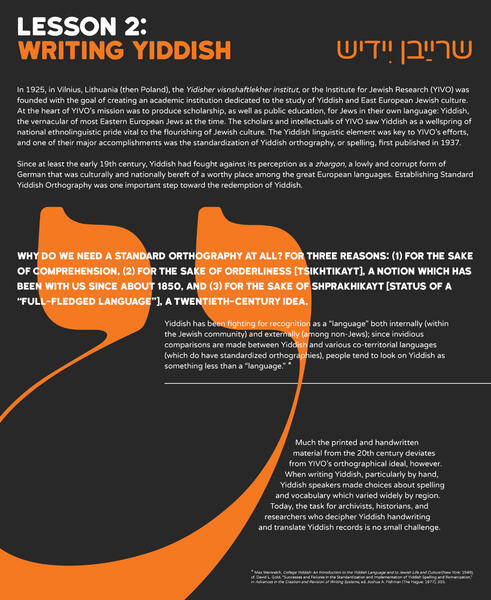

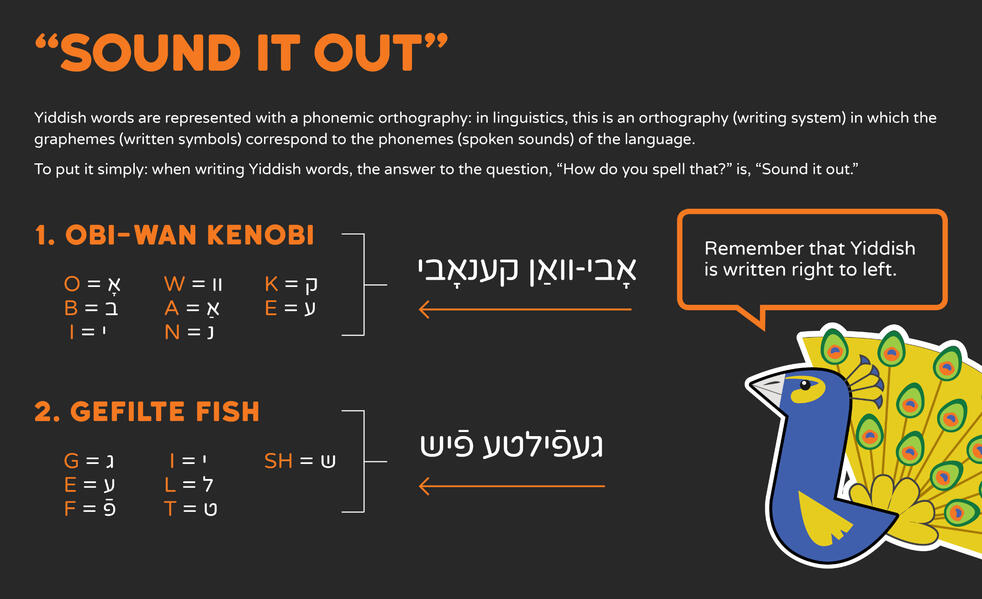

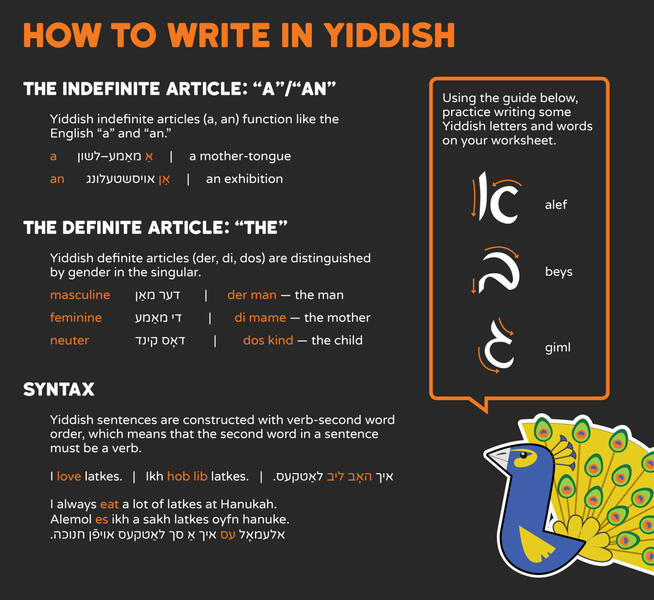

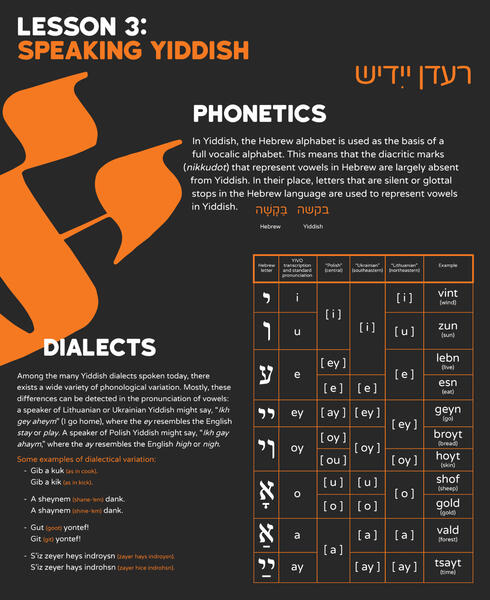

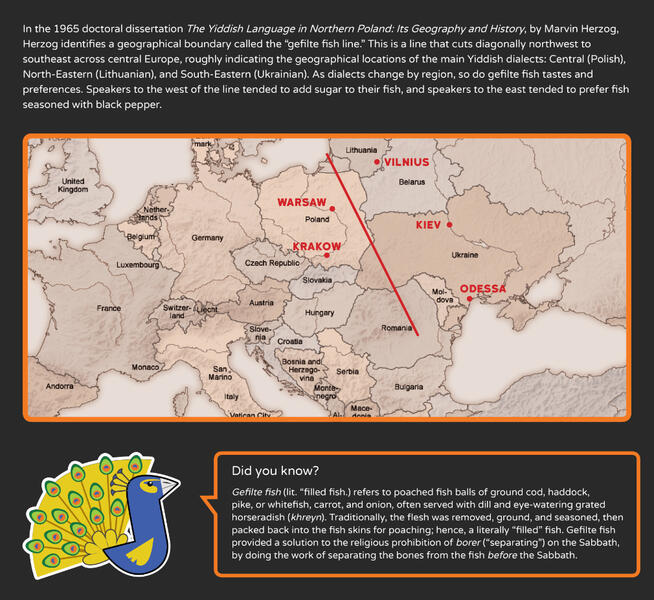

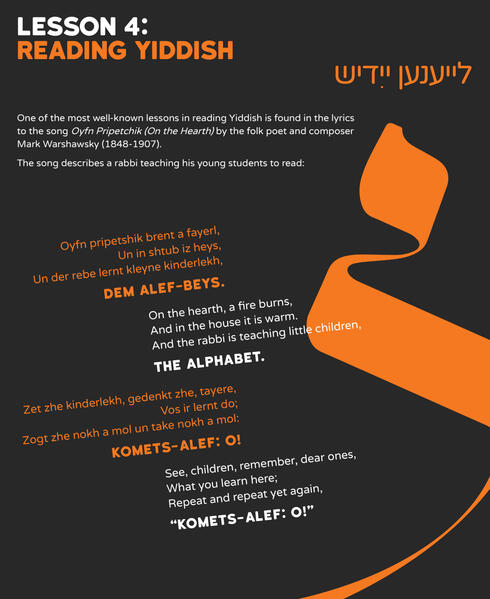

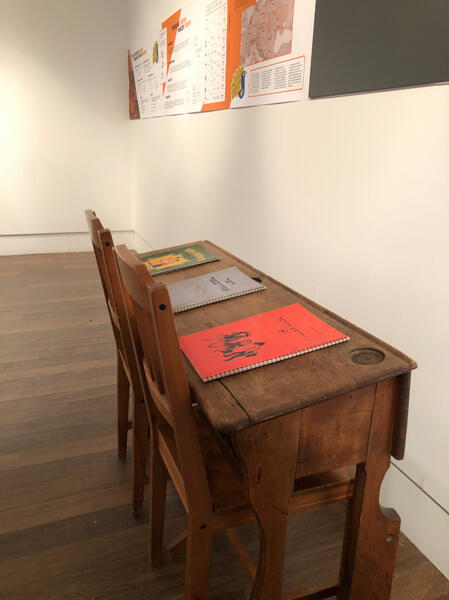

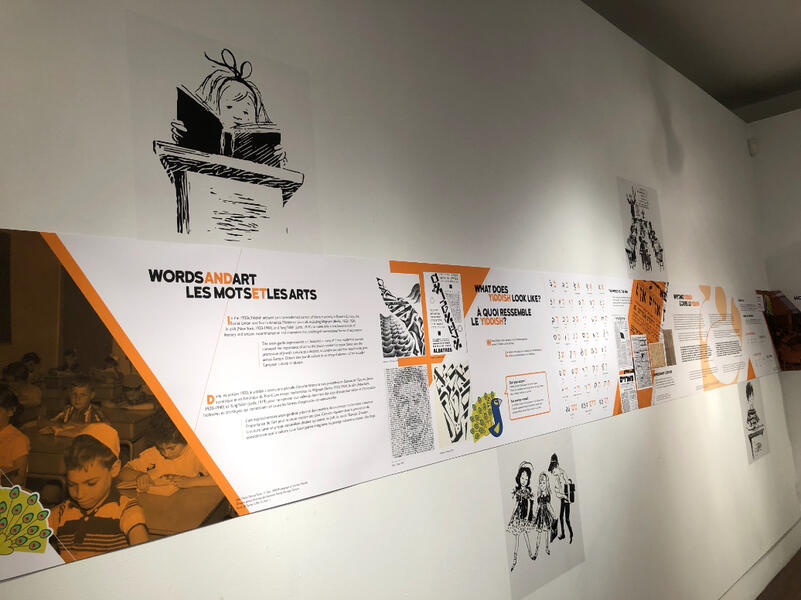

Inspired by the kheyder, the traditional form of Jewish elementary education in Eastern Europe, this exhibit invited visitors to imagine themselves as pupils learning at the Yiddish kheyder, where they could explore some of the basic skills required to engage with Yiddish: how to read it, how to write it, how to speak it, and how to identify what it looks and sounds like. In this kheyder, The University of Toronto libraries’ rich Yiddish collection was the melamed (teacher). On display, there was everything from children’s primers to doctoral dissertations, with a worksheet to track your progress throughout.Built into the concept of a Yiddish kheyder is a theoretical challenge that encourages us to think about space. As we know, learning and teaching Yiddish was not the express purpose of the traditional kheyder, where instruction instead largely emphasized liturgical and Biblical texts; as Max Weinreich wrote, “No one was ever flogged for not knowing Yiddish.” This Yiddish kheyder, then, is a new creation. It is a Yiddish space rooted in history, but not found in historical space or time. Rather, this Yiddish kheyder is a creation for this space and this time, inviting visitors to reflect on the fact that increasingly, 21st century Yiddish spaces have moved from the street, the home, and the shul into the classroom, the library, and the museum.

This exhibition was generously sponsored by the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, the Al and Malka Green Yiddish Studies Program, and the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies. It drew upon the holdings of the University of Toronto library system and the documentary resources held at the Ontario Jewish Archives Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre.

CANADIAN LANGUAGE MUSEUM, APRIL – JUNE 2019

Yiddish Spring

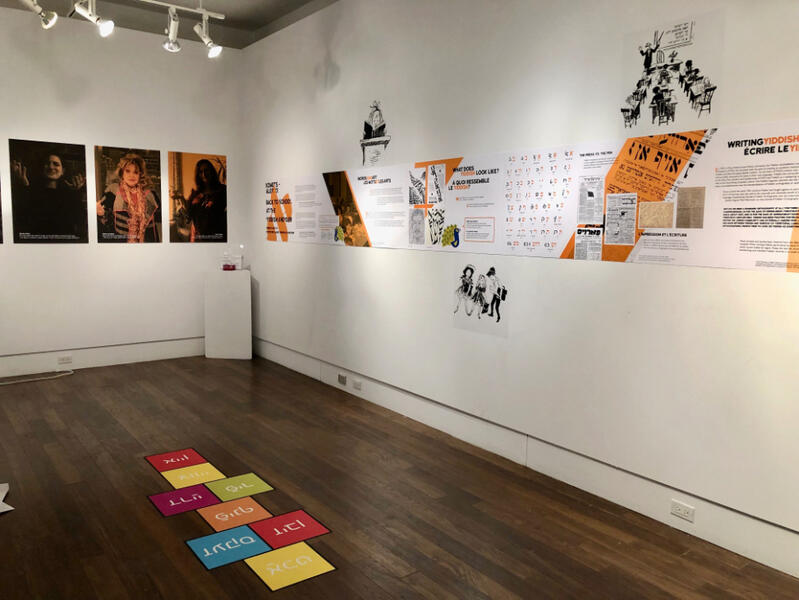

From April 4 to June 27, 2019, the Yiddish kheyder enjoyed a second run as part of a larger exhibition called “Yiddish Spring at the Canadian Language Museum.”To accommodate the new space, the kheyder design received a makeover: taking advantage the larger space, we redesigned the exhibition and created a makeshift “classroom,” complete with Yiddish hopscotch! To make it even more fun, we enlarged illustrations from the classic Yiddish children’s primer Yidishe kinder (New York, 1959), so the children travelled with visitors through the exhibition.

“Yiddish Spring” was a multimedia exhibition presented by the Ashkenaz Festival that, in addition to the visual kheyder material, include a sound installation by the brilliant Berlin-based musician Paul Brody. Brody drew on his work with both contemporary Jewish music and radio documentaries to create “The Music of Yiddish Blessings and Curses.” Brody interviewed eight Yiddish speakers and recorded their voice-melodies as they recited blessings and curses, later composing a 17-minute, five-part suite that mirrored and played upon those melodies. “I became fascinated by how my interviewee’s voice-melody often shifted from conversational to a melodic, almost singing voice, through the uttering of a blessing or a curse,” said Brody.

In praise of

“Borden’s vision dramatically alters concepts of place in relation to what Yiddish is and what it can be.”

— Rebecca Margolis, Chair of Jewish Civilisation, Monash University

Yiddish-related items such as books, newspapers, and photographs are given a second life by being digitized and made available to a wide public, which allows for accessibility far beyond what has ever been possible. Using interactive tools, digital technology can help to bridge the deep chasms generated by time and geographic distance. When asked about the future of the Yiddish book, Borden suggests a model of digital and interactive maps that is being applied to medieval manuscripts, which are also increasingly becoming digitized. Borden created a second and more ambitious exhibit at the Robarts Library involving Yiddish books, this time with an online component built in from the outset. “Komets-alef: o! Back to School at the Yiddish Kheyder”(2018) invites its viewers to become student participants in an imagined school. Online participants can download a Yiddish worksheet and open related images as well as audio files. The exhibit offers a model for accessible and engaging interactive encounters with Yiddish. Borden has further explored theoretical questions in the second incarnation of her exhibit, held at the Canadian Language Museum in the summer of 2019. The website page about the exhibit notes:'Built into the concept of a Yiddish kheyder is a theoretical challenge that encourages us to think about space. As we know, learn-ing and teaching Yiddish was not the express purpose of the traditional kheyder, where instruction instead largely emphasized liturgical and Biblical texts; as Max Weinreich wrote, “No one was ever flogged for not knowing Yiddish.” This Yiddish kheyder, then, is a new creation. It is a Yiddish space rooted in history, but not found in historical space or time. Rather, this Yiddish kheyder is a creation for this space and this time, inviting visitors to reflect on the fact that increasingly, 21st century Yiddish spaces have moved from the street, the home, and the shul into the classroom, the library, and the museum.'Borden’s vision dramatically alters concepts of place in relation to what Yiddish is and what it can be. Here Yiddish books exist as mate-rial culture, and as such represent objects in an evolving relationship with people over time and space.Rebecca Margolis, Yiddish Lives On: Strategies of Language Transmission (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2023, 225-227).

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden

other projects

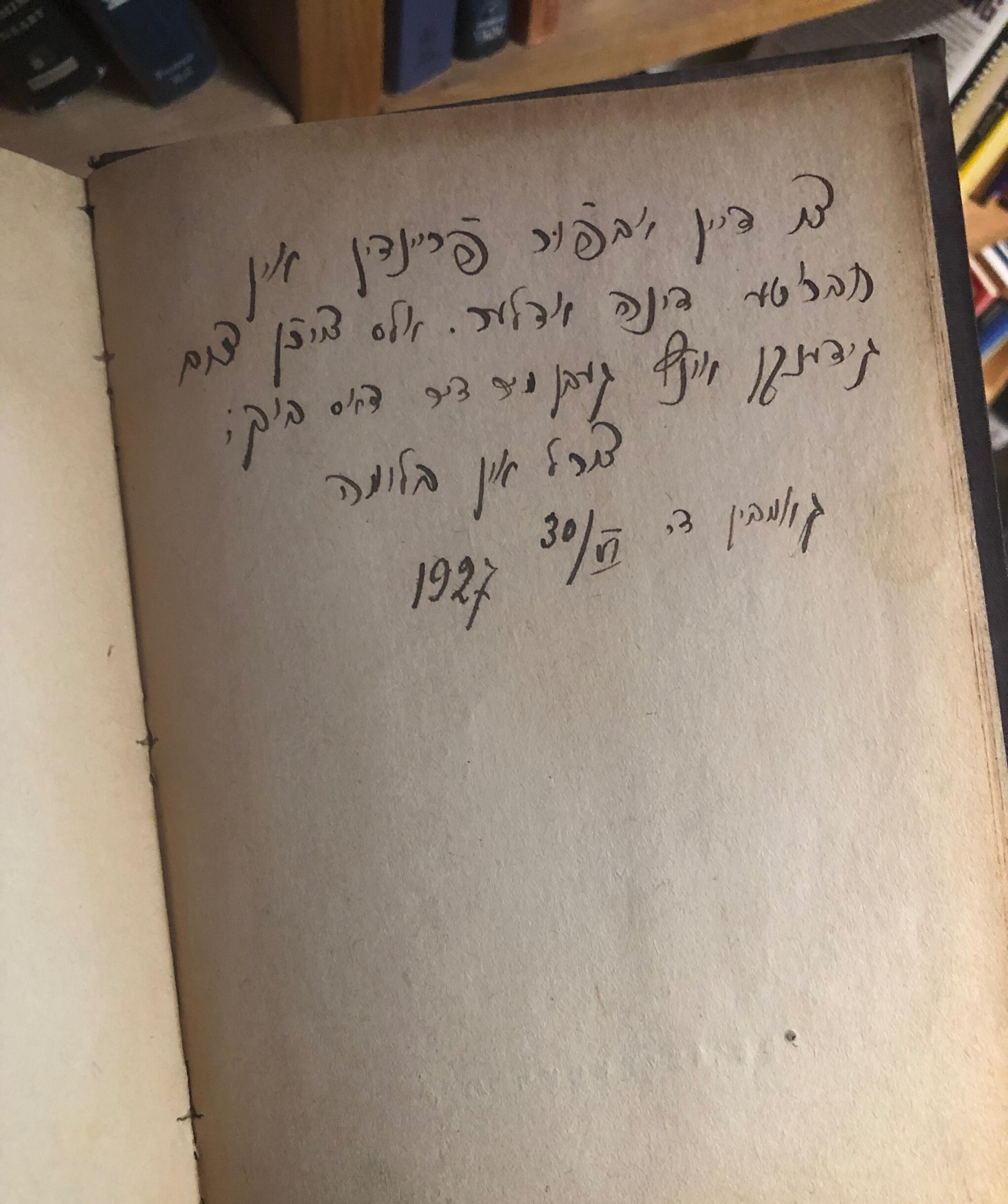

Ontario Jewish Archives

The Ontario Jewish Archives, Canada’s largest repository of Jewish life, holds an untold number of Yiddish documents, objects, inscriptions, and other material. Since 2019, I have been excavating this collection one item at a time with weekly social media posts featuring an archival object paired with a Yiddish Word of the Week. Explore some of my posts below.

Herring

A research subject I developed in 2017 and nurtured in dozens of community settings over the years, herring has earned me the enviable title, “herring lady.” Read some of my herring work here:

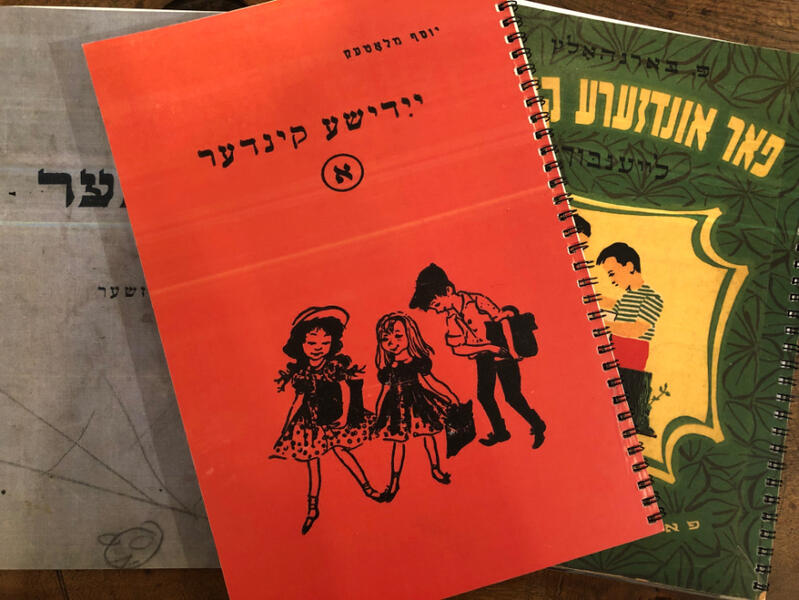

Book Collection

In 2019 I began collecting Yiddish primers, basal readers, workbooks, and other educational material for children in Yiddish secular schools. My collection coalesced as the Toronto Workmen’s Circle, one of the city’s leading Yiddish cultural organizations, sold its building and packed up what remained of its Yiddish supplementary school, the I.L. Peretz Shule. The collection harks back to the Peretz school’s heyday, the 1950s and 1960s, when Toronto saw an enormous influx of Jewish immigrants, nearly all Yiddish-speaking Holocaust survivors, and many who enrolled their students in Yiddish school as a means of affirming their identities and rebuilding their lives. The collection as a whole reflects postwar efforts in Yiddish language pedagogy in a scarcely-researched Yiddish cultural center at a moment when enrolment in Yiddish schools was waning, commemoration of the Holocaust was transforming Jewish identity, and the generation of Jews born in Toronto after the Holocaust was rapidly assimilating into Canadian culture. Books inscribed with children’s doodles, workbooks filled with answers to homework, vocabulary flashcards, song booklets, card games, and other material from this long-faded era of Yiddish education are a vibrant testament to the urgency of maintaining language in the wake of indescribable loss.

WINNER

2020 HONEY & WAX BOOK COLLECTING PRIZE

In the fall of 2020, I won the Honey & Wax Book Collecting Prize for my singular collection of Yiddish children’s readers, primers, and educational materials, and my essay, “Building a Nation of Little Readers: Twentieth Century Yiddish Primers and Workbooks for Children.”Honey & Wax Booksellers, based in Brooklyn, NY, awards this prize to women book collectors in the United States, aged 30 or younger.Read the essay, view the collection, and see the Paris Review’s announcement here:

Interviews and media

THE SCHMOOZE, THE PODCAST OF THE YIDDISH BOOK CENTER

Catching up with Miriam Borden, winner of the Honey & Wax Book Collecting Prize, and Heather O’Donnell of Honey & Wax. In announcing the prize, Honey & Wax noted, "Borden's collection represents an impressive effort of historical preservation and an inspiring example of how a collection that began as something personal becomes a collective resource."

THE BIBLIO FILE PODCAST, HOSTED BY NIGEL BEALE

January 24, 2021: “Book Collector Miriam Borden on rescuing the Yiddish language”An exploration of Yiddish past and present, how language shapes culture, and what it’s like to preserve that culture once the language is gone.

FINE BOOKS & PRESS MAGAZINE: INTERVIEW

For their Bright Young Collectors series, Fine Books & Collections speaks to Miriam Borden about her award-winning Yiddish collection.

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden

Get in touch

For questions or more information about working with Miriam on a project, please contact Miriam Borden by email below:

Miriam Borden is a doctoral student in Yiddish at the University of Toronto. She is a researcher and translator of Yiddish archival materials at the Ontario Jewish Archives, and leads walking tours of Kensington Market, Toronto’s historic Jewish neighbourhood. She has consulted for the Yidlife Crisis web series and been featured on Vaybertaytsh: A Feminist Podcast, in Yiddish. She is an Oral History Field Fellow and 2019 - 2020 Pedagogy Fellow at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Miriam sits on the board of the Ashkenaz Festival of Jewish Culture. For her piquant public presentations on pickled fish, she is fast becoming known as the ”herring lady.”You can follow Miriam and her award-winning Yiddish book collection on Instagram @bikher_chickAlso catch her taking over the Ontario Jewish Archives Instagram account every Friday for the #YiddishWordoftheWeek. Check out @ontariojewisharchives for your weekly dose of Yiddish!

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden

Thank you

I'll be in touch soon!

© 2017 - 2025 Miriam Borden